Science of Scars: Why Some Wounds Heal Flawlessly While Others Don’t

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

You probably have a scar, or you know someone who does. In some situations, a wound heals and fades without leaving any visible trace; however, in other instances, a scar eventually forms and remains. This occurs because The Science of Scars investigates why certain wounds heal more effectively than others, demonstrating that the body repairs damage through different mechanisms. Furthermore, some scars result in more than just physical discomfort. Indeed, they may also affect emotional well-being, since they can cause feelings of self-consciousness or anxiety, particularly when they appear on the face.

What is a Scar?

A scar forms as part of the skin’s natural repair process. When the skin is cut or damaged, for instance, it repairs itself by growing new tissue that pulls together the wound and closes the gap. In fact, scar tissue is made primarily of collagen, a strong protein that gives skin its structure. Sometimes, the repair process works smoothly, and the new tissue blends almost invisibly into the surrounding skin. However, at other times, the result is a more noticeable scar — thick, raised, sunken, or discolored.

“Healing doesn’t have to look magical or pretty. Real healing is hard, exhausting, and draining. Let yourself go through it.”

- About half of people worldwide have at least one scar.

- Scars can itch, burn, or feel dry.

- Many people worry their scar will not fade, which affects confidence.

- The market for scar treatments keeps growing, showing how much people care about healing well.

Understanding scar formation helps you protect both your skin and your mental well-being.

Science of Scars

Scar Tissue vs. Normal Skin

The science of scars explains why scar tissue looks and feels different from normal skin. Under a microscope, normal skin has a basket-weave pattern of collagen. This gives your skin strength and flexibility. In scar tissue, collagen fibers line up in parallel rows. This makes the tissue stiffer and less stretchy.

| Parameter | Normal Skin | Scar Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen Orientation Index | 0.26 (random) | 0.44 (parallel) |

| Bundle Packing (distance) | Higher (looser) | Lower (denser) |

Scar tissue also has fewer special proteins and cells. It feels thicker and sometimes itchy. The science of scars shows that these changes make scars stand out. They may look shiny or pale. They do not work as well as normal skin. You might notice that scars do not sweat or grow hair.

The science of scars helps you see why some wounds heal smoothly, while others leave a mark.

Why Scars Form

You get a scar when your body repairs a wound with new collagen. Specifically, if the wound is deep and reaches the dermis, your body makes more collagen to fill the gap. As a result, this extra collagen forms a scar. In fact, deeper wounds almost always leave a mark because the skin cannot rebuild its normal pattern.

Additionally, some body parts scar more than others. For example, areas that move a lot, like elbows or knees, put stress on healing skin. Consequently, this stress tells fibroblasts to make more collagen, which then leads to thicker scars. Similarly, burns, cuts, and surgical wounds that go deep into the skin also raise your risk for a scar.

Your genes play a role, too. Some people get thicker scars because of their family history. People with darker skin tones may get raised scars, called keloids, more often.

On the other hand, proper wound care helps. For instance, if you keep a wound clean and avoid pulling on the skin, you lower your chance of a big scar. Interestingly, nerves in your skin also send signals that affect how fibroblasts work, which can change the texture of the scar.

Finally, fibroblast activity changes from one area to another. For example, wounds inside your mouth heal with almost no scar because the fibroblasts there help skin grow back fast and smooth. By contrast, on your back or arms, fibroblasts make more collagen, so scars are more likely.

Visualization Table

| Aspect | Wounds with Minimal Scarring | Wounds with Prominent Scars |

|---|---|---|

| Fibroblast Type | Pro-regenerative | Pro-fibrotic |

| Myofibroblast Level | Low | High |

| Collagen Pattern | Weak alignment | Strong alignment |

| Mechanical Tension | Low | High |

| Outcome | Smooth healing | Thick scar |

Overall, you can see that the way your body heals depends on many things. In fact, fibroblasts, collagen, wound depth, movement, and even your genes all play a part.That is why some wounds heal with barely a trace, while others leave a scar that lasts.

Types of Scars

You see many types of scarring. Each scar looks and feels different. Dermatologists sort scars into groups. Here are the main types of scarring you might notice:

- Fine line scars– These scars are thin and straight. You often get them after surgery.

- Wide scars– These scars stretch and look pale. You may see them on the belly or after weight changes.

- Atrophic scars– These scars sink below the skin. Acne and chickenpox often cause them.

- Scar contractures– These scars tighten the skin. Burns can lead to contracture scars.

- Raised skin scars– These include hypertrophic and keloid scars. Raised scars feel firm and may itch.

- Intermediate scars– These scars do not fit into other groups.

Keloid and Hypertrophic

Firstly, keloid and hypertrophic scars are both raised. Generally, you may find them after cuts, burns, or surgery. However, hypertrophic scars stay inside the wound area. They look red and thick, but they may shrink over time. Conversely, keloid scars grow past the wound edges. They can get bigger and, unlike hypertrophic scars, they rarely go away on their own.

Moreover, some people get keloid scars more often. Specifically, burn patients often get hypertrophic scars. Indeed, up to 91% of burn patients develop them.

The Wound Healing Process: From Injury to Repair

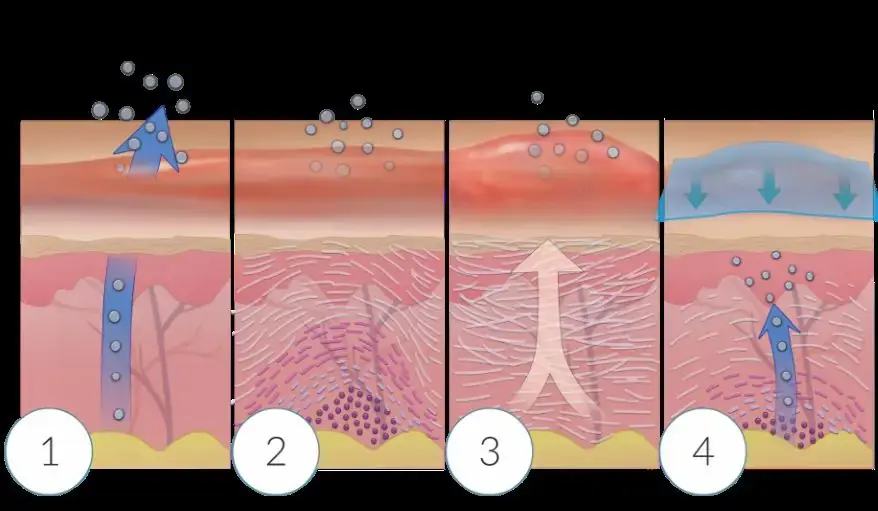

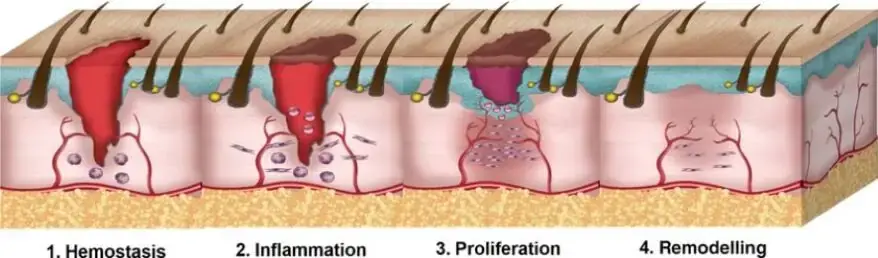

When you get hurt, your body starts working fast. The wound healing process follows four main steps. Each step helps your skin repair and protect you.

1: Hemostasis

Your body reacts in seconds. Blood vessels tighten. Platelets rush in and form a clot. This stops bleeding and creates a barrier. Fibrin forms a mesh to hold everything together.

2: Inflammation

This step lasts up to a week. Firstly, white blood cells arrive to the wound. Then, they clean up germs and dead cells. As a result, you might see swelling, redness, or feel heat. Meanwhile, growth factors help guide healing. Afterward, macrophages join in after a few days. Consequently, they clear debris and send signals for new tissue.

3: Proliferation

This phase starts around day four. Generally, it can last three weeks or more. During this time, fibroblasts move in and make collagen. Meanwhile, new blood vessels grow. As a result, granulation tissue fills the wound. Subsequently, skin cells cover the area again. Finally, collagen types change as healing continues.

4: Remodeling

This step takes months or even years. Collagen fibers reorganize and strengthen. Scar tissue forms. The area gets stronger but may look different.

Here’s a quick look at the timeline:

| Phase | Timeline | Main Events |

|---|---|---|

| Hemostasis | Seconds to minutes | Clot forms, bleeding stops |

| Inflammation | Up to 7 days | White blood cells clean and protect |

| Proliferation | 4 days to 3 weeks+ | Collagen builds, skin regrows |

| Remodeling | Months to years | Scar matures, tissue strengthens |

The wound-healing process is complex but follows a clear path. Your body works hard to repair and protect you every time you get injured.

Healing Differences

Genetics and Age

Evidently, you might notice that some people get a scar easily, while others heal with barely a mark. Indeed, genetics play a big role in this. Because your genes control how much collagen your body makes and how your immune system reacts, scar outcomes can vary greatly. Moreover, some families see more scars, especially keloids, chiefly because of inherited traits. Specifically, certain genes, like TGF-beta and HLA alleles, can make you more likely to form a thick scar. Furthermore, if you have a genetic disorder like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, your skin may heal poorly and leave unusual scars.

Age also changes how your skin heals. As you get older, your skin gets thinner and loses strength. Blood flow slows down, and your skin does not repair as fast. Older adults often heal slower, but their scars may look less red or raised than those in younger people. Kids and teens sometimes get thicker scars because their skin is more active and produces more collagen.

| Factor | Effect on Healing | Effect on Scarring |

|---|---|---|

| Genetics | Controls collagen, inflammation | Higher risk for keloids, thick scars |

| Age (young) | Fast healing | More red, raised scars |

| Age (older) | Slow healing | Less red, flatter scars |

Scar-Free Healing

Some tissues heal almost without a scar. The inside of your mouth is a good example. Wounds there heal fast and leave little or no scar. Scientists found that oral tissue has special fibroblasts that act more like those in a baby’s skin. These cells help control inflammation and make healing smooth. Fetal skin also heals without scars. Babies in the womb can repair skin with no mark left behind. Their skin uses less blood flow and has different growth factors.

Researchers want to copy these scar-free healing tricks for everyone. They study how to change adult skin to heal more like fetal or oral tissue. New ideas include using stem cells, blocking certain signals, or changing how fibroblasts work. Some scientists test special bandages that reduce stress on the skin. These new treatments may help you heal with less scarring in the future.

Why Some Wounds Heal Badly

Some wounds just do not heal well. You might see a scar that is thick, red, or raised. Many things can slow healing or make scars worse. Local problems at the wound site play a big part. If your skin does not get enough oxygen, healing slows down. Infections can cause more swelling and damage. If you have a foreign object in the wound, your body cannot repair it well. Poor blood flow, like in venous insufficiency, also makes healing harder.

Your body’s health matters too. Chronic diseases like diabetes slow healing. Diabetes can cause low oxygen, weak cells, and poor blood flow. If you take certain medications like steroids or chemotherapy, your skin repairs more slowly. Poor nutrition and smoking also hurt your body’s ability to heal.

Here are some common reasons wounds heal badly:

- Excessive inflammation during healing

- High-density fibrin clots that trigger more scar tissue

- Growth factors from platelets that push fibroblasts to make extra collagen

- Prolonged healing and too many new blood vessels

- Severe infection or dead tissue that increases inflammation

Risk factors for bad scarring include:

- Deep or large burns

- Wounds on the chest, arms, or feet

- Young age, especially in children

- Darker skin tones

- Infection or slow healing

- Family history of thick scars

- Mechanical stretch or movement at the wound site

The Science Behind Flawless Healing

You might wonder why some wounds heal so well. Your body uses a smart system to repair skin. Wound healing depends on how your cells and signals work together.

When you get a cut, many cell types jump into action. Keratinocytes cover the wound. Fibroblasts build new support. Endothelial cells make new blood vessels. Neutrophils and macrophages fight germs and clean up. Special γδ T cells help control the repair. Each cell has a job. They talk to each other using growth factors like EGF, HGF, and FGF. These signals tell cells when to move, grow, or stop.

Inflammation plays a big part. If your body controls it well, you get smooth healing. Too much inflammation leads to thick scars. Some animals and babies have the ability to heal wounds with almost no scars. Their bodies keep inflammation low and balance cell signals.

New treatments help you heal better. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) uses safe energy to kill germs and boost healing. It helps new blood vessels grow and lowers swelling. Stem cell therapy gives your skin new helpers. These cells release growth factors and help build new tissue. Electrical microcurrent therapy uses gentle currents to speed up repair and reduce pain.

Flawless healing is possible when your body controls inflammation, uses the right signals, and gets the help it needs from new therapies.

Why Most Wounds Leave Scars

You might wonder why your skin often leaves a scar after an injury. Some tissues, like the inside of your mouth or a baby’s skin, heal without scars. Most wounds on your body do not heal this way.

Why do scars form?

- Adult skin repairs itself by making new collagen. This process is fast but not perfect.

- Fetal skin heals with less inflammation and more organized collagen.

- Fetal fibroblasts move quickly and make collagen at the same time. Adult fibroblasts work slower and delay collagen production.

- Hyaluronic acid is higher in fetal skin. It lowers inflammation and helps smooth healing.

- Gene expression in fetal wounds supports cell growth and less scarring.

- In adults, excess collagen and poor organization lead to scars.

- Pro-fibrotic signals like TGF-β push fibroblasts to make more collagen and cause inflammation.

- If your body cannot balance collagen breakdown, scars get thicker.

New research brings hope for scar-free healing.

- Doctors use massage, pressure garments, and silicone gel to help scars fade.

- Advanced treatments include microneedling, stem cell therapy, and platelet-rich plasma.

- Medicines like statins and ACE inhibitors show promise for reducing scars.

- Scientists test drugs like verteporfin for full skin restoration in animals.

- Future therapies may use hair follicle signals to turn scar cells into fat cells, helping skin heal smoothly.

Conclusion

You can help your skin heal better by following simple steps.

- Keep wounds clean and moist.

- Cover wounds to protect them.

- Avoid picking at scabs.

- Protect scars from sun with sunscreen.

- Use silicone gel or sheets for raised scars.

- Massage scars gently after a month.

- Act early for best results.

References

- Monstrey, S., Middelkoop, E., Vranckx, J. J., Bassetto, F., Ziegler, U. E., Meaume, S., & Téot, L. (2014). Updated Scar Management Practical Guidelines: Non-invasive and invasive measures. Journal of Plastic Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 67(8), 1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.011

- Guo, S., & DiPietro, L. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125

- Sorg, H., & Sorg, C. G. G. (2022). Skin Wound Healing: Of Players, Patterns, and Processes. In European Surgical Research (Vol. 64, Issue 2, pp. 141–157). S. Karger AG. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528271

- Hunt, A. H. (1960). Wound Healing. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591576005300113

Additionally, to stay updated with the latest developments in STEM research, visit ENTECH Online. Basically, this is our digital magazine for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Furthermore, at ENTECH Online, you’ll find a wealth of information.

Disclaimer: We do not intend this article/blog post to provide professional, technical, or medical advice. Therefore, please consult a healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet or lifestyle. In fact, we only use AI-generated images for illustration and decoration. Their accuracy, quality, and appropriateness can differ. So, users should avoid making decisions or assumptions based only on the text and images.