10 Foundational Principles of Quantum Computing – Part I

Quantum computing uses the principles of quantum mechanics to handle information, and therefore enabling it to tackle complex problems that are beyond the capabilities of classical computers. Specifically, this capability leads students to embark on a fascinating exploration of cutting-edge science and technology. Moreover, the physical properties of matter or systems, like energy, are not continuous but exist in discrete, quantized amounts.[1]

So, a quantum represents the smallest measurable unit of a physical property. Furthermore, a quantum state describes a quantum system, which in turn allows us to calculate observable characteristics such as position or momentum. Particularly, in this article series, I will explain 10 foundational principles of quantum computing.

Undoubtedly, quantum mechanics provides the theoretical foundation for understanding quantum systems. Furthermore, it explains how matter and energy behave at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles, such as electrons and photons.[2]

Surely, quantum computing paves a new way of building computers. Specifically, this requires use of the unique principles of quantum mechanics. These principles, however, are very different from what we see in everyday life. As a result, quantum computing creates computers that work in a fundamentally different way. Consequently, they have the potential to be much more powerful than the computers we use today.

The foundational principles of quantum computing are

- Wave Particle Duality

- Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

- Pauli Exclusion Principle

- Qubit

- Superposition

- Measurement

- Interference

- Entanglement

- Coherence

- Decoherence

1. Wave Particle Duality [3]

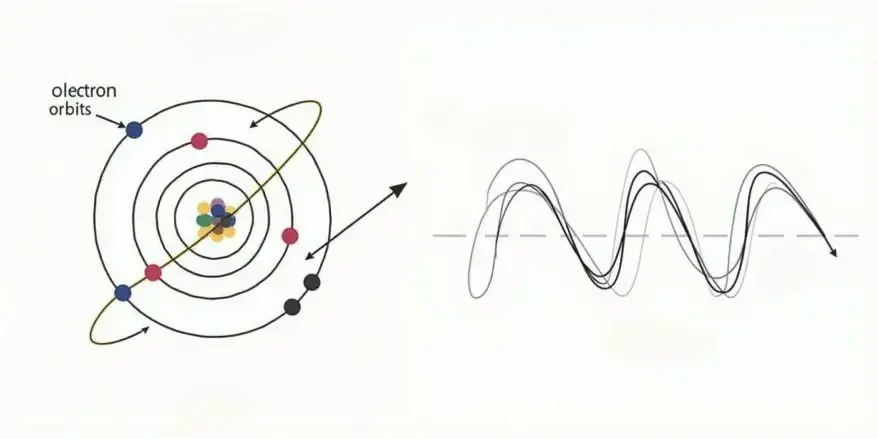

In 1923, a French scientist named Louis De Broglie proposed a fascinating idea. He suggested that

tiny particles, like photons (light particles) and electrons, can behave in two ways at the same time: as particles and as waves.

As particles, they are like tiny balls that you can imagine as being in a specific spot and having properties like mass and charge. But as waves, they spread out in space and create patterns, much like the ripples you see when you toss a stone into water.

The diagram in Fig. 1 shows this dual behavior: electrons acting as particles and as waves. This idea helps us understand how matter behaves on an incredibly small scale.

2. Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle [4]

It states that

It is impossible to know both the exact position and momentum of an electron simultaneously, as they cannot be simultaneously measured with absolute precision

Position: It is the specific location of an object at a specific time.

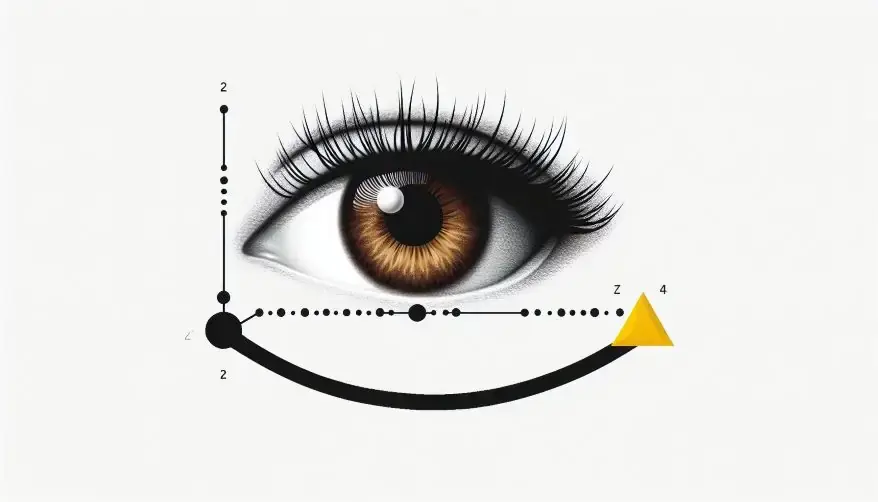

Momentum: It is a measure of how much motion an object has. Also, it depends on two things: how heavy the object is (its mass) and how fast it is moving (its velocity), Fig. 2. Also, we calculate it by multiplying the mass by the velocity, 𝑝 = 𝑚 × 𝑣 (mass times velocity).

Illustration of Heisenberg Principle

For example, if you try to know exactly the position of a tiny particle like an electron, you will not be able to know exactly how fast it is moving. And if you know exactly how fast it is moving, you will not be able to know its exact position.

Mathematically, it is expressed as: Δx⋅Δp ≥ ℏ/2

where:

- Δx: Uncertainty in position

- Δp: Uncertainty in momentum

- ℏ: Reduced Planck’s constant (h/2π)

This concept can be illustrated as shown in Fig. 3.

Furthermore, imagine you want to measure where an electron is located. Then, to accomplish this, you need to shine a photon (a tiny particle of light) on the electron. When the photon hits the electron, it bounces back to the measuring device, like a microscope. However, photons carry energy and momentum. When the photon collides with the electron, it transfers some of its momentum to the electron. Thus it makes the electron move, changing its path. Because the photon and electron have similar amounts of energy, the collision makes it harder to figure out exactly where the electron is. Therefore, when every time we measure the electron’s position, we disturb its momentum, making its speed and direction uncertain. Eventually, measuring one property (like position) affects another property (like momentum), making it impossible to know both with perfect accuracy.

3. Pauli Exclusion Principle [5]

Surprisingly, this fundamental principle of quantum computing was proposed by the scientist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925. It states that

No two electrons in an atom can be at the same time in the same state or configuration

Indeed, no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. These four quantum numbers together uniquely define the state of an electron in an atom. Also, quantum numbers are like a set of “addresses” or “coordinates” that describe where an electron is and what it is doing. These coordinates tell you things like:

- The electron’s energy level (principal quantum number n)

- The shape of the orbit it moves in (Azimuthal quantum number l)

- The orientation of that orbit (magnetic quantum number ml)

- The direction of the electron’s spin (which can be either up or down) (spin quantum number ms).

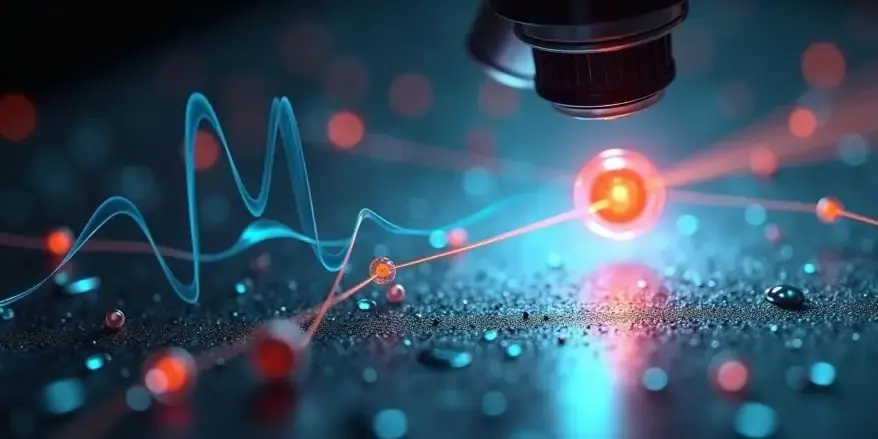

4. Qubit [6]

A qubit (short for quantum bit) is the basic unit of information in quantum computing.

Instead of just being 0 or 1, as in classical computing, a qubit can be in multiple states at the same time.

Specifically, a process known as photoexcitation allows an electron to absorb energy from light. This happens when light (made up of tiny particles called photons) hits the electron and gives it enough energy to jump from a lower energy level to a higher one, usually within an atom or molecule.

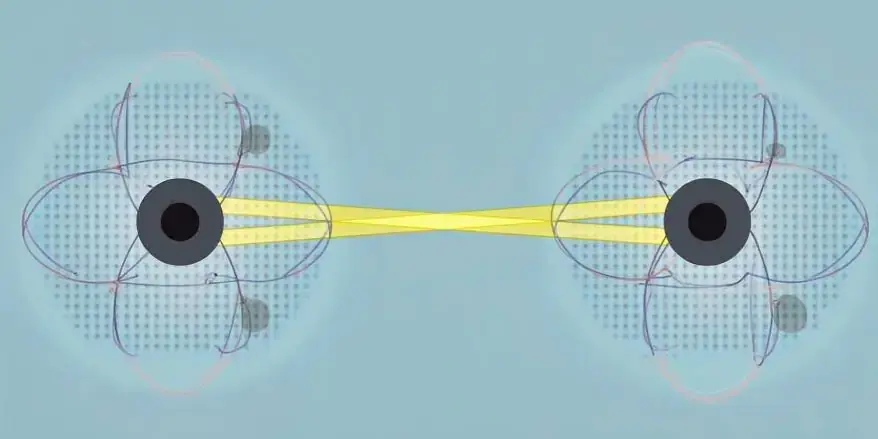

Particularly, we can make a qubit by using an atom that has two possible energy levels. Indeed, we can think of these levels as the two states of the qubit. The ground state (lowest energy level) represents |0⟩. The excited state (higher energy level) represents |1⟩. Fig. 4 illustrates this. These states allow qubits to store and process information in ways that regular bits cannot, which is what makes quantum computing so powerful!

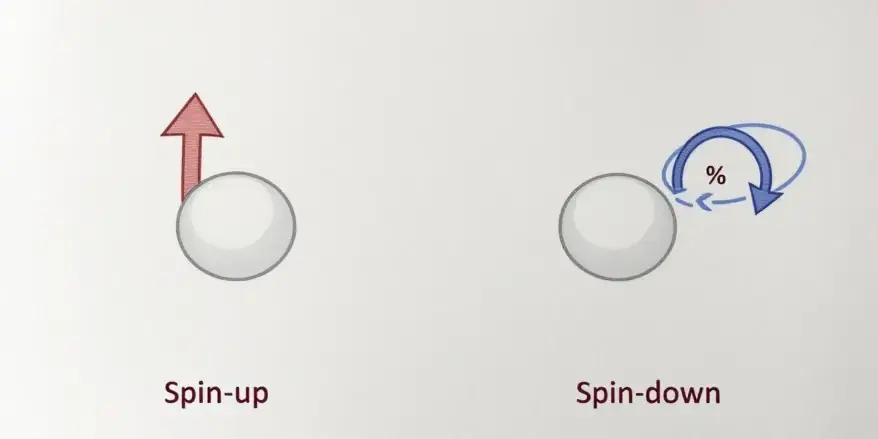

What are spin-up and spin-down states? [7]

Surprisingly, in quantum computing, the spin-up and spin-down states of an electron can show the two possible states of a qubit. This is shown in Figure 5.

Spin-up (↑) can represent the state |0⟩.

Spin-down (↓) can represent the state |1⟩.

Quantum computers use these spin states to encode information.

5. Superposition [8]

Superposition means a quantum particle can exist in multiple states simultaneously until it is observed or measured.

Example 1:

As per this principle of quantum computing, an electron can be in multiple positions around an atom at the same time.

Indeed, a qubit can be in one of two states: |0⟩ or |1⟩, or it can be in a combination of both states at the same time, which is called a superposition.

Furthermore, for a light pulse to affect the qubit, the frequency (or color) of the light must match the energy difference between the two states of the qubit, like |0⟩ and |1⟩. Also, we refer to this match as resonance. When the light pulse has the right frequency, the qubit can absorb the energy and change its state, as shown in Fig. 6. In simple terms, when a light pulse interacts with the qubit, it can make the qubit jump from one state to another, depending on the energy the light provides.

Example 2:

When you flip a coin, you are not sure whether it is head or tail? When we see how the spinning coin lands, we can be sure of it. But while the coin is still spinning in the air, it is neither heads nor tails. Hence, there is some probability of both, as shown in Fig. 7.

Indeed, a quantum coin spins in a simultaneous superposition of “heads” and “tails.” When it lands, it is either heads or tails.

In the next part of this article, we will see the remaining 5 foundational principles of quantum computing.

References

[1] Rieffel, E., & Polak, W. (2000). An introduction to quantum computing for non-physicists. ACM Computing Surveys, 32(3), 300–335. https://doi.org/10.1145/367701.367709

[2] Feng, G., Lu, D., Li, J., Xin, T., & Zeng, B. (2023, October 13). Quantum computing: principles and applications. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.09386

[3] Chang, D. C. (2021). Review on the physical basis of wave–particle duality: Conceptual connection between quantum mechanics and the Maxwell theory. Modern Physics Letters B, 35(13), 2130004. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0217984921300040

[4] Busch, P., Heinonen, T., & Lahti, P. (2007). Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Physics Reports, 452(6), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2007.05.006

[5] Smart, S. E., Schuster, D. I., & Mazziotti, D. A. (2019). Experimental data from a quantum computer verifies the generalized Pauli exclusion principle. Communications Physics, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0110-3

[6] Bravyi, S., Dial, O., Gambetta, J. M., Gil, D., & Nazario, Z. (2022). The future of quantum computing with superconducting qubits. Journal of Applied Physics, 132(16). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0082975

[7] Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M., & Petta, J. R. (2023). Semiconductor spin qubits. Reviews of Modern Physics, 95(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.95.025003

[8] Uttam, S. (2012). Introduction to quantum information Processing. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 119–144). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-385491-9.00004-6

Additionally, to stay updated with the latest developments in STEM research, visit ENTECH Online. Basically, this is our digital magazine for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Furthermore, at ENTECH Online, you’ll find a wealth of information.